EDITION WANDELWEISER RECORDS

> CD catalogue

> Dante Boon

_____________________________________________________________________

<< >>

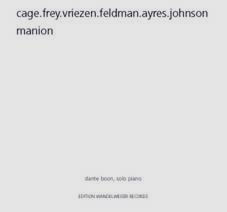

cage.frey.vriezen.feldman.ayres.johnson

manion

| order reference:

medium: composer: performer: |

EWR 1001/02 CD John Cage / Jürg Frey /Samuel Vriezen / Morton Feldman / Richard Ayres / Tom Johnson / Michael Manion Dante Boon (piano) |

|

|

|

>> Review Brian Olewnick (blog) Pianist and composer Dante Boon often programs his recitals as webs. He likes to put compositions of great diversity in style and technique side by side. However, myriad connections can always be found between pairs of pieces, and these give the whole a subtle coherence. This is also how his first CD is organized, presenting pieces by seven composers spanning almost a century of music. But the most important unifying element of this disc is Dante's own musical personality and approach to the piano. Two poles are important for Dante's playing. On the one hand he is drawn towards the musical discipline of the Cageian tradition and its concern with objectivity in sound. On the other hand, early Romanticism, particularly German song repertoire, is important to him. For many listeners, these poles may seem like opposites. For Dante, however, there is no contradiction. In his playing, precision of technique and conceptual clarity are expressions of a passionate engagement with sounds and their progression as melody. Here, melodic thought reveals the sonic concept and it is the concept that is sung. For example, Tom Johnson's Tilework for Piano, probably the most austere piece in this collection, is a systematic exploration of the ways in which a fifteen-beat phrase can be covered by a simple rhythmical three-note pattern that appears at five different speeds. Those five layers by themselves have a percussive quality. But in his performance, Dante is more interested in the surprising melodic figures that result from different combinations of the layers, and his articulation and phrasing stress the melodic aspect over the separation of layers. Likewise, in a seemingly chaotic piece such as John Cage's Etude no. 2, Dante manages to let expressive melody surface suddenly, while giving the piece's complex, anarchic texture a sense of balance and composure. Similarly, the nervous inner motions of Richard Ayres' No. 8 are performed with a concentration that draws us into their expressive detail, and the sudden bursts of pure movement in my own series of Possible World pieces gain in brilliance through Dante's refined articulation. (No. 5, scored for 1 to 4 pianos and allowing for variety in form, is played twice in different versions.) Cage's early Two Pieces, works of great melodic invention, fit Dante's playing naturally. The other pieces presented here are all based on chords and chord progressions. Here, too, there is much melodic interest, and Dante brings a clear balance to all sounds, making them sing. Jürg Frey's Sam Lazaro Bros turns out to have an almost Schubertian atmosphere, though listening to it I'm equally reminded of 16th-century choral progressions. In John Cage's One, a piece that requires the pianist to carefully organize his phrasing, even the chords themselves already seem to sing at times - particularly some of the louder ones. In Morton Feldman's Last Pieces, there is always a subtle local melodic logic to the progression of seemingly unconnected sounds, which allows Dante to bring great depth to his playing in the ultra soft range. The program closes with Michael Manion's Music for Solo Piano, dedicated to Dante, which draws its chords out into long, sometimes subtly swinging pulsating moments. Over its extended duration, it goes through no more than about twenty chords that form one long melodic arch, taking over half an hour to get to its surprising and very beautiful final cadence. Samuel Vriezen > top |